Michael T. Rietveld1,2, and Peter Stubbe3,

NB. DETTE INNLEGGET GJENSTÅR DET REDIGERING.

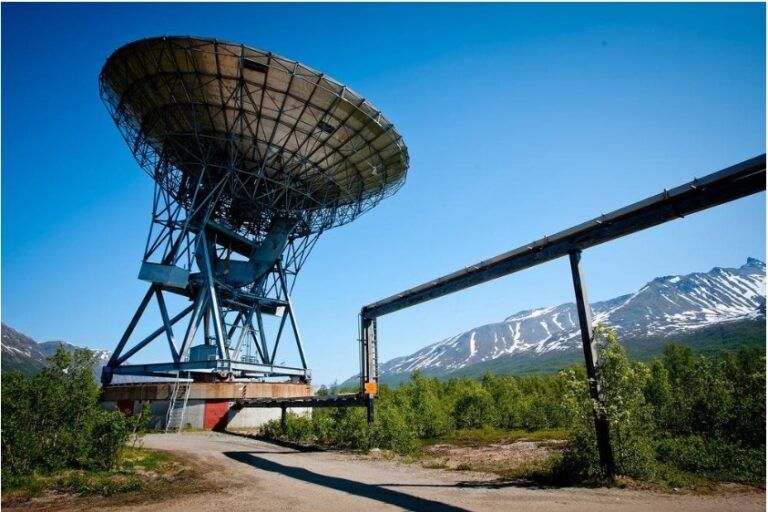

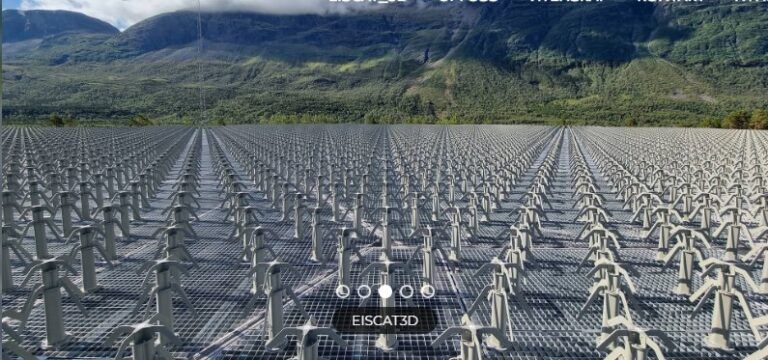

History of the Tromsø ionosphere heating facilityMichael T. Rietveld1,2, and Peter Stubbe3,1EISCAT Scientific Association, Ramfjordmoen, 9027 Ramfjordbotn, Norway2Department of Physics and Technology, UiT The Arctic University of Norway,9037 Tromsø, Norway3Max-Planck-Institut für Aeronomie (now known as Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research inGöttingen), 37191 Katlenburg-Lindau, GermanyretiredCorrespondence: Michael T. Rietveld (mikerietveld20@gmail.com)Received: 1 November 2021 – Discussion started: 16 November 2021Revised: 3 March 2022 – Accepted: 5 March 2022 – Published: 22 April 2022Abstract. We present the historical background of the construction of a major ionospheric heating facility,“Heating”, near Tromsø, Norway, in the 1970s by the Max Planck Institute for Aeronomy; we also detail the facility’s subsequent operational history to the present. Heating was built next to the European Incoherent ScatterScientific Association (EISCAT) incoherent scatter (IS) radar facility and in a region with a multitude of diagnostic instruments used to study the auroral region. The facility was transferred to EISCAT in January 1993 andcontinues to provide new discoveries in plasma physics and ionospheric and atmospheric science to this day. Itis expected that Heating will continue operating along with the new generation of IS radar, called EISCAT_3D,when it is commissioned in the near future.1 IntroductionIn the following, we present the history of a major ionospheric research facility that played a very important part inboth of the authors’ scientific careers. The second author wasinvolved right from the start of the project until the transferof the facility from the Max Planck Institute for Aeronomy tothe European Incoherent Scatter Scientific Association (EISCAT) in 1993. The authors worked together for several yearsup to this date, after which the first author managed the facility until his retirement in 2020. This history, which concentrates on the administrative and technical aspects but alsomentions important scientific collaborations and results, isbased on the authors’ personal memories and documents thatare available to them but which may not be easily accessibleto all readers.2 Background and conceptionThe history of ionospheric heating experiments started in theearly days of radio with the Luxembourg effect (Tellegen,1933): the modulation of a powerful radio transmitter wasimparted in the ionosphere on another radio wave transmission. The explanation was that the powerful radio wave couldheat the free electrons in the plasma which makes up theionosphere and, thus, change the properties of the medium.The ionosphere is the ionized part of the upper atmosphere,extending from about 70 km to several hundred kilometres.By injecting high-power radio waves into this plasma, it became possible to use the ionosphere as a plasma laboratorywithout the restriction of boundary walls which limit somelaboratory plasma experiments. Through these experiments,a better understanding of plasma physics was made possibleand a new technique to learn more about the ionosphere itselfwas provided. A major advance was made in the early 1970 swith a heating facility in Boulder, Colorado, USA, showinga plethora of unexpected ionospheric phenomena that couldbe triggered by powerful high-frequency (HF) waves (as outlined in Utlaut, 1974). This spawned international interest,especially in the Cold War era, during which time radio communication via the ionosphere was still important and ionospheric irregularities played an increasingly important rolePublished by Copernicus Publications.72 M. T. Rietveld and P. Stubbe: History of the Tromsø ionosphere heating facilityin understanding radar echoes from natural phenomena aswell as synthetic objects. At the same time, the incoherentscatter (IS) radar technique for measurement of ionosphericplasma properties was developing rapidly, with US facilitiesin Arecibo (Puerto Rico) and in Millstone Hill and Chatanika(Alaska), and European radars in France and the UK eitheroperating or being planned. An advanced tristatic Europeanradar was also in the planning for northern Scandinavia toinvestigate the auroral ionosphere. The Max Planck Society, one of the major scientific research organizations in Germany, was already a partner in the planning of this radar andbecame one of the six associates in the European IncoherentScatter Scientific Association (EISCAT). Two Max Planckinstitutes were involved: the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, in Garching, and the Max Planck Institute for Aeronomy (MPAe), in Katlenburg-Lindau (nowthe Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, in Göttingen) (Haerendel, 2016). Ian Axford, who had just beenappointed as the new director of MPAe in 1974, stronglysupported and influenced the development of EISCAT andsuggested building an ionospheric heating facility. About thistime, similar facilities were being built near Arecibo and inthe former Soviet Union, both at low to mid-latitudes. TheMPAe had a long history in the area of HF radio researchand techniques for the purpose of studying the ionosphereand upper atmosphere (e.g. Czechowsky and Rüster, 2007);therefore, designing and constructing a high-power HF transmitting facility was well within the competence of the institute. With the new director (Axford) came a number of international guest researchers who helped develop the sciencecase for an ionospheric heater as well as advising on technical issues. Some of these were Fred Hibberd from Australia, Jules Fejer from the USA (who was also an externalscientific member of MPAe), and Dick Dowden from NewZealand. The project was led by Prof. Peter Stubbe and Dipl.Phys. Helmut Kopka (Dipl. Phys. stands for the German degree of Diplom-Physiker, which is approximately equivalentto a masters degree in physics). Other scientists from MPAewho were closely involved with “Project Heating”, as it wascalled, were Prof. Harry Kohl, Dr. Gerhard Rose, and Dipl.Phys. Hans Lauche.3 Funding, construction and inaugurationThe planning and design of Project Heating started in 1975.The total cost of the facility was estimated to be 6 millionGerman marks (DM) at that time, equivalent to EUR 3 million. Approximately one-third of this amount (for development, operating, and personnel costs) came from the operating budget of MPAe, one-third was from an investment fromthe Max Planck Society, and the remaining one-third wasfrom an investment from the German Research Foundation(Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft – DFG). The amount didnot include the salary costs of the staff who worked on theFigure 1. Aerial photo of the Heating antennas and IS radars at theRamfjordmoen site from 1996. (Photo credit: Fjellanger WiderøeAS)project at MPAe. The project was formally a joint project between MPAe and the University of Tromsø (UiT): funding,design, and construction were the responsibility of MPAe,while UiT, especially Asgeir Brekke and Reidulv Larsen, arranged local permits and infrastructure, such as the buildings.UiT was also the main Norwegian partner in EISCAT (seeHolt, 2012). For several reasons, the Heating site was chosen to be next to the new EISCAT radars in Ramfjordmoen,about 30 km south of Tromsø by road. MPAe and UiT werealready involved in the EISCAT radar project, which wouldbe a major diagnostic for Heating, and there were many common infrastructure items, such as communication and theelectric power line that was specially installed to supply bothprojects. An important feature of the location in the Arctic ascompared to mid-latitudes or low latitudes is that the Earth’smagnetic field is close to vertical; this is advantageous forstudying many plasma physical phenomena. Figure 1 showsan aerial view of the Heating facility next to the EISCATradars. A history of the EISCAT system was recently published by Wannberg (2022).Design concepts for the facility were outlined by Kopkaet al. (1976), and these were largely adhered to in the finalfacility. The design of the facility was challenging. To coverthe wide frequency range from 2.7 to 8 MHz, three antennaarrays, each of 6 × 6 crossed full-wave dipoles were built tothe same design, but the lengths, spacing and height aboveground were scaled by √2 between arrays. The full-wave antennas were rhombically broadened to provide a wider bandwidth than single-wire antennas. The centre frequency was3.31 MHz for Array 1, 4.71 MHz for Array 2, and 6.63 MHzfor Array 3, each with a 37 % bandwidth. Each array wasfed by high-power coaxial cables, with a total length of ca.50 km, from a central building housing 12 transmitters of upto 100 MW each. The gain of each array was 24 dBi at themid-frequency (dBi is the maximum gain of the radiationHist. Geo Space Sci., 13, 71–82, 2022 https://doi.org/10.5194/hgss-13-71-2022M. T. Rietveld and P. Stubbe: History of the Tromsø ionosphere heating facility 73Figure 2. Schematic diagram showing the layout of antennas and major infrastructure at the Ramfjordmoen site (to scale). The red diagonallines in the HF arrays represent the full-wave antennas attached to wooden masts at each end (small red crosses). The feed points of eachcrossed-dipole antenna is where the red lines cross each other. The black squares in HF Array 1 show the original 23 m tall wooden masts towhich the low-frequency antennas were attached (until 1985), and the red crosses in Array 1 show the 12 m tall wooden masts added around1989 for the modified array containing higher-frequency antennas similar to Array 3. The Dynasonde (HF sounder), housed in the samebuilding as the HF control room, and its associated antennas are an integral part of the Heating facility. The EISCAT IS radar antennas andbuildings are shown at the upper right. The large blue crosses show the crossed half-wave dipoles of the 2.78 MHz MF (medium-frequency)radar transmitting antenna, suspended between masts (small blue crosses). The ionosonde tower supports the transmitting antenna for theUniversity of Tromsø’s digisonde. The Morro array is an antenna for a 56 MHz MST (mesosphere–stratosphere–troposphere) radar fromthe University of Tromsø. The green double line shows the road, and the unlabelled boxes are buildings or huts with optical and otherinstruments.pattern in decibel compared with that of an isotropically radiating antenna), resulting in a maximum effective radiatedpower (ERP) of 300 MW. Figure 2 shows a schematic diagram of the antenna arrays as well as other relevant instruments and buildings in the Ramfjordmoen site. Commercialhigh-power coaxial cables and other components were tooexpensive; thus, in-house designed and built air-filled coaxial cables, baluns, power splitters, quarter-wave transformers, stubs, and motor-driven coaxial switches were producedfrom aluminium pipes and specially designed castings andfabrications (see Fig. 3). This was a highly innovative butalso risky undertaking. The design worked very well electrically, but it required retrofitting of an air dryer and compressor to feed dry air into the whole system in order to preventthe ingress of moisture as well as the installation of manymore wooden supports under the coaxial lines in order tosurvive the harsh winter conditions of northern Norway. Theaccumulation of up to 2 m of snow and ice during a wintercould bend, deform, or break some of the aluminium components, and the subsequent thaw in the spring meant that partsof the lines could be under water. Nearly all of the connectors are aluminium, so the prevention of moisture ingress inthe transmission lines is very important, which the compressor and dryer achieved successfully. In spite of the air dryerand extra wooden supports under the cables, maintenance ofthis coaxial cable feed system would remain a fairly labourintensive annual task each summer.A conducting ground plane was never installed, as it wasfelt to be unnecessary given the moist ground conditions atRamfjordmoen, so the calculated ERP assumed a perfectlyconducting ground. In hindsight, a ground plane might haveincreased the actual ERP, as subsequent modelling reportedin Senior et al. (2011) suggests that, using measured values ofground conductivity and dielectric constant, the actual ERPis approximately 75 % of that calculated assuming a perfectground.The transmitters were state-of-the-art vacuum tube transmitters with a wideband solid-state driver and automatictuning and impedance-matching system employing variablevacuum capacitors and switchable inductors between frehttps://doi.org/10.5194/hgss-13-71-2022 Hist. Geo Space Sci., 13, 71–82, 202274 M. T. Rietveld and P. Stubbe: History of the Tromsø ionosphere heating facilityFigure 3. The fabricated coaxial cables and towers in one row ofantennas of Array 2 in spring of 2010. The vertical tubes, whichare part of the tower supporting the antenna, are also coaxial cablesacting as quarter-wave transformers supplying the radio frequency(RF) current to the antenna. Array 3 has an identical design but issmaller in size. Originally, Array 1 had similar antennas, larger insize, but these were modified after the storm in 1985. (Photo credit:Michael T. Rietveld)quency bands. The main power amplifier was a linear, watercooled Siemens tetrode RS2052CJ vacuum tube with variable voltage power supplies using thyristors. A prototypedesign from Siemens was used to build the transmitters, including power supplies, in-house. The wideband solid-statedriver was designed to deliver ca. 1.5 kW to the power amplifier tube and was built in-house. It was found that theimpedance matching to the tube was not good; thus, animpedance-matching filter needed to be designed and constructed, which turned out to be the equivalent of an engineering masters thesis (Diplomarbeit in German). Figure 4shows some of the open transmitter cabinets and three people who were closely involved in the early part of the project.The radio frequency (RF) waveform was produced usingthe new (at the time) HP3325 A synthesizers, with one foreach of the 12 transmitters and an additional one as phasereference. These were controlled by computer from a Commodore PET (personal electronic transactor) microcomputerrunning a combination of assembler and BASIC (Beginners’All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) language programswith a specially developed interface to the essential transmitter hardware. For modulation of the transmitter output,another microcomputer, a Texas Instruments TM 990 programmed in assembler language, was used with 12 digitalto-analogue converters and other special hardware to provideexternal control voltages to the HP synthesizers to vary theiramplitude and phase. Low-frequency synthesizers could alsobe used to amplitude modulate the RF waveform from the HPsynthesizers. Figure 5 shows a block diagram of the transmission system and the power distribution to the various antennaarrays.Figure 4. Three important people involved in the construction ofHeating. The photograph shows, from left to right, technician Helmut Gegner and scientists Jules Fejer and Helmut Kopka in thetransmitter hall in 1979. Four open 100 kW transmitters are visible,which were used in the first experiments. (Photo credit: MPAe)Construction of the facility in Ramfjordmoen occurred between 1978 and 1980. This involved long periods of workby teams of up to about 10 engineers, technicians, and otherworkers from MPAe, who stayed in the main accommodation and control building in Ramfjordmoen. In anticipationof large teams having to stay for long periods, this buildingwas designed to be relatively spacious and well equipped.The MPAe staff who designed and built parts of the facility were Dr. Rainer Kramm (electronics and software),Richard Zwick, and Lothar Bemmann. Heinz-Günther Kellner, Eberhard Schäfer, Karl Schreiber, Rudi Pabst, and WilliButscheck built and assembled much of the hardware, andHelmut Gegner and Klaus Eulig assembled, maintained, andoperated the facility for the duration of the project underMPAe ownership. Many other workers from MPAe were involved in the construction of parts in Katlenburg-Lindau andthe subsequent assembly work in Tromsø for shorter periods.In the control building, an advanced HF radar developedat the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration(NOAA, Boulder CO), called the “Dynasonde”, was also installed. This instrument was and still is essential to determine the state of the ionosphere continuously and in realtime, independent of the EISCAT IS radars, which are notalways operating. It was also an important diagnostic instrument to measure the effects of heating the ionosphere. J. W.(Bill) Wright and R. (Dick) Grubb were valuable collaborators in the set-up and use of this versatile instrument. Thecomputer hardware and operating and analysis software werelater upgraded such that this instrument is still providing advanced high-quality ionospheric data to this day (Rietveld etal., 2008).There was an official inauguration in September 1980, bythe director of MPAe, Ian Axford, and the rector of the University of Tromsø, Prof. Yngvar Løchen; guests from theHist. Geo Space Sci., 13, 71–82, 2022 https://doi.org/10.5194/hgss-13-71-2022M. T. Rietveld and P. Stubbe: History of the Tromsø ionosphere heating facility 75USA, Bill Gordon and Tor Hagfors (the latter of which wasthe director of EISCAT at this time), who were both pioneers in the ionospheric heating field, were also present. Atthis stage, there had already been experiments performed using the available, finished transmitters out of the final 12transmitters. The first experiments were carried out with theNorwegian partial reflection (PRE) system of UiT (August1979), followed by the first very low frequency (VLF) excitation experiments with Dowden’s system (March 1980), theexcitation of micropulsations with Hans-Joachim Lotz andJürgen Watermann (September 1980), and the first anomalous absorption experiments with Tudor Jones’ group fromthe University of Leicester, UK (October 1980). These firstexperiments are described in summarized form in Stubbe etal. (1980). Another early result from August 1980 was themeasurement of fast attenuation of the reflected HF wavewhich was explained in terms of the parametric decay instability and a slower attenuation by heater-induced striations(Fejer and Kopka, 1981). The original duration of ProjectHeating was limited to the end of 1987 but, because ofthe successful results obtained, it was decided to extend theproject until the end of 1992.A comment is in order about the name of the facility. AtMPAe, it was a project, simply called “Heating” because ofthe main physical effect of heating the electrons in the ionosphere that it could produce. This was not an acronym, although it has sometimes been spelled with all capital letters.After the transfer to EISCAT, it was also called Heating or theHeating facility. Because thermal heating of electrons is notthe only effect of the powerful HF wave, it is sometimes simply called the HF facility or HF pump because the HF wavescan excite and pump various plasma instabilities, thereby energizing electrons to suprathermal energies.4 The first decade of discoveriesThe results of the first 2–3 years were quickly published andsummarized in a review paper by Stubbe et al. (1982), followed by another review 3 years later (Stubbe et al., 1985).Many important scientific discoveries were made in the first10 years of operation. One of the highlights was the exploration of the process by which ionospherically induced currents in the lower ionosphere (ca. 70–110 km) generate extra low frequency (ELF) to very low frequency (VLF) radiowaves in the audio-frequency range and below. With measurements from ELF/VLF and micropulsation receiving systems installed by R. L. Dowden from Otago University, NewZealand, at a UiT field station in Lavangsdalen, about 17 kmfrom the heater site, along with theory and modelling, theauthors could explain the characteristics and mechanismsinvolved in the generation process of these low-frequencywaves. The first author became involved in these experiments as a post-doctoral scientist in 1981 after completinga doctoral degree on VLF wave research at Otago University. ELF/VLF wave propagation experiments were also performed with satellite receivers in the ionosphere and magnetosphere and (unsuccessful) attempts at conjugate wave reception at the Australian Antarctic base in Mawson. Latercollaboration with Richard Barr from New Zealand exploredEarth–ionosphere waveguide propagation and the evaluationof different modulation techniques to explore the efficiencyof such wave generation, both experimentally and with modelling.Lavangsdalen was also the site of the accidental discoveryof another important phenomenon – stimulated electromagnetic emissions (SEE) – consisting of the generation of secondary HF waves due to plasma processes in the ionosphereunder the action of the powerful pump wave (Thidé et al.,1982; Stubbe et al., 1984). This discovery opened up a majorresearch area at all heating facilities (e.g. Leyser, 2001).Early experiments were also performed with the local partial reflection experiment (PRE) from UiT as well as HFdiagnostics from the group at the University of Leicesterled by Tudor Jones. Research from this group led to manytheses and papers, such as those by Terry Robinson, AlanStocker, and Farideh Honary. Naturally, the EISCAT UHF(ultra-high-frequency) radar and, later, the VHF radar whenit came on line in 1985, were used as a new diagnostic instruments. Much scientific interest was directed at IS radarexperiments and Heating, where the Earth’s magnetic fieldwas near-vertical, in contrast to the interesting results coming out of the Arecibo facility, where the magnetic fieldwas near 45◦. For near-field-aligned HF pumping, the Langmuir turbulence results were expected to be much strongerand, indeed, the experimental results exceeded expectationsand provided a source of controversy. There was fruitful exchange between theory and experiment from these experiments. For these IS radar diagnostics, which usually involvedhigh time and spatial resolution observations of strong coherent signals induced in the ion and plasma line spectrum,special modulations and detection algorithms had to be developed with very different requirements from the usual ISmeasurements of the undisturbed plasma. These programmeswere developed mostly by Harry Kohl and Terrence Ho fromMPAe. Collaborations were developed with researchers frommany countries. These included Tor Hagfors, Brett Isham,Cesar La Hoz, Frank Djuth, Mike Sulzer, and Shanti Basu.There were several cooperative projects with scientists fromthe former Soviet Union in various institutes such as the Polar Geophysical Institute in Murmansk, IZMIRAN (Instituteof Terrestrial Magnetism, Ionosphere and Radiowave propagation) near Moscow, and the Institute of Radio Astronomyin Ukraine. Some campaigns after 1990 involved scientistsbringing diagnostic instruments with them from the formerSoviet Union, which was impossible in the days of the ColdWar.From the start of Project Heating, it was planned to flyrocket instrumentation through the heated region (Stubbeet al., 1978) from the Norwegian rocket base at Andøya.https://doi.org/10.5194/hgss-13-71-2022 Hist. Geo Space Sci., 13, 71–82, 202276 M. T. Rietveld and P. Stubbe: History of the Tromsø ionosphere heating facilityFigure 5. Diagram showing the transmission system and how the power was distributed from one transmitter (a) to six crossed dipoles ineach of the antenna arrays before the storm in 1985 and (b) to 24 crossed dipoles in the rebuilt Array 1 from 1990. After 2008, the HP3325Asynthesizers were replaced by direct digital synthesizer boards.The principle investigator for this HERO (HEating ROckets)project was Dr. Gerhard Rose from MPAe, with collaboratorsfrom the Fraunhofer Institut für Physikalisch Messtechnik(Institute for Physical Measurement Techniques) Freiburg,Germany; the Norwegian Defense Research Establishment;and the University of Oslo. The HERO project was the firstproject especially designed to undertake in situ measurements of the HF-generated Langmuir waves and their influence on the surrounding plasma. One of the four flights flownin 1982 resulted in important measurements of the HF wavefield strength, electron and ion temperatures, and suprathermal electrons excited by the heater (Rose et al., 1985), butthe EISCAT radar was, unfortunately, not operational during this flight. A special modification to one of the antennaarrays had to be made in order for a rocket to be able tofly through the heated region, as rockets could not be flownover the Norwegian mainland. Phase delay coaxial feed lineswere constructed for the mid-frequency Array 2 such thatHist. Geo Space Sci., 13, 71–82, 2022 https://doi.org/10.5194/hgss-13-71-2022M. T. Rietveld and P. Stubbe: History of the Tromsø ionosphere heating facility 77the heater beam could be tilted 13◦ westwards towards theplanned rocket apogee, in addition to a tilt of 7.5◦ northwardsachieved by normal phasing of the transmitters. These linescould be switched in and out within a few minutes, in thesame way that the transmitters could be switched betweendifferent antenna arrays. This westward tilting ability wasalso used after the rocket campaigns for some satellite radio beacon experiments, but the coaxial lines of this phaseshifter were later removed to reduce maintenance. However,the remaining switches and control hardware may still havea useful future, as will be mentioned below.The most important results from the first phase of operation of the Heating facility, led by researchers from MPAe,have been summarized in Stubbe (1996).5 A storm and antenna array reconfigurationThe three antenna arrays were all used depending on whichfrequency was optimum for the particular science goal. Manyexperiments in which plasma instabilities were excited required pump frequencies near the O-mode critical frequencyin the F layer, which has a daytime maximum that varieswith solar radiation and the solar cycle. Other experimentsthat rely on maximum ohmic heating of the lower ionosphereare best with lower frequencies. Thus, Array 1, the lowestfrequency and largest array, was used mostly for VLF/ULF(ultra-low-frequency) modulation and other D region experiments. On 25 October 1985, extremely high winds during astorm seriously damaged about 75 % of the 36 antenna towers in Array 1, leaving all of the wooden masts intact. Noneof the towers in the other two arrays were damaged. The aluminium towers in all three arrays were of identical construction, differing only with respect to height: 12 m in Array 3,16 m in Array 2, and 23 m in Array 1. They were anchoredonly at the top and bottom with no guy wires in between,which was probably the reason for the failure: the Array-1towers were too tall and, hence, not rigid enough such thatthey bent under the force of the wind.Rather than rebuild the array in its original form, it was decided that the lower-frequency band could be dispensed with,as VLF/ULF wave generation experiments could also bedone at higher frequencies, and Landau damping of the Langmuir waves generated by parametric instabilities at theselower frequencies would be too high to make them interesting. On the other hand, one lost the opportunity to examineeffects at the second gyro-harmonic, and one also lost flexibility with respect to the frequency choice near solar minimum, during which time the critical frequencies are oftenvery low. It was decided to add 120 wooden masts of 12 mheight to the existing 23 m high wooden masts and to install144 crossed full-wave dipole antennas in a 12 × 12 configuration for the 5.5–8 MHz frequency band, within the samearea as the 6×6 original low-frequency antennas (see Fig. 2).This gave the array a gain of 30 dBi, which corresponds toan ERP of 1200 MW compared with the 24 dBi of Array 3;thus, Array 1 was sometimes called the super heater. The resulting beam was, therefore, narrower than that of the othertwo arrays, and it could not be tilted as far off zenith. Experiments with the rebuilt array started in 1990 and continued under MPAe leadership until the transfer to EISCAT inJanuary 1993. Although no new phenomena were discoveredwith the higher-gain array, the higher power density proveduseful for many experiments, especially in the D region ormesosphere as later experiments were to show. A more detailed description of the HF facility, as it was then, is givenin Rietveld et al. (1993).6 Transfer to EISCAT and user expansionAfter nearly 10 years of successful discoveries and exploration, it was decided that MPAe would end Project Heating. This was suggested by Ian Axford, as the emphasis ofresearch at the institute was increasingly moving towardsspace-based instrumentation, and ionospheric research activity was decreasing. This was in line with a general policywithin the Max Planck Society to fund research projects onlyfor a limited time and to start new ones. A transfer of the facility to EISCAT Scientific Association was offered, and after a scientific case (Robinson et al., 1989) was prepared bya group of interested scientists led by Prof. Terry Robinson,the facility was formally transferred to EISCAT in January 1993

The first author, who had been employed at EISCAT

since 1987, became responsible for running the facility from

1993 until December 2020, and, initially, two engineers were

dedicated with the operation and maintenance of the Heating

division of EISCAT. Gradually, the staff at Ramfjordmoen

shared the tasks necessary to operate the IS radars and Heating as required by the changing user demands of the different facilities. For example, much effort was spent on building

the EISCAT Svalbard Radar (ESR) in the early to mid 1990s

which diverted scientific interest and operations to the polar

cap region.

The transfer to EISCAT resulted in a larger user group

continuing heating experiments that nominally used 200 h

of heater time per year but which varied between 100 and

300 h depending partly on the solar cycle. Fewer experiments

were possible when the F region critical frequency was low

during solar minimum. Most experiments were in conjunction with the IS radar as the major diagnostic instrument

(in many cases) or as one of several diagnostics. Improvements in diagnostic instrumentation; the deployment of new

instruments; and improved radar coding, modulation, and

data storage associated with advances in computing technology led to new discoveries that were impossible or difficult to achieve in the first decade of operation. Some examples are (1) the discovery that heating the lower ionosphere

can weaken or suppress polar mesospheric summer echoes

(PMSE) observed by the VHF (224 MHz) radar (Chilson et

https://doi.org/10.5194/hgss-13-71-2022 Hist. Geo Space Sci., 13, 71–82, 2022

78 M. T. Rietveld and P. Stubbe: History of the Tromsø ionosphere heating facility

al., 2000) and (2) the production of light emission from the

heated ionosphere (Brändström et al., 1999). These two very

different areas of research, namely study of the mesospheric

dusty plasma and energetic electron acceleration, have remained as major topics of research up to the present time.

A technique developed in the former Soviet Union that

uses only the powerful HF waves to measure ionospheric and

atmospheric parameters by the production of artificial periodic irregularities (API) (Belikovich et al., 2002) was successfully applied in the auroral ionosphere for the first time

by combining the Heating facility as a transmitter and the

Dynasonde as a receiver (Rietveld et al., 1996b). Later, more

sophisticated experiments by Vierinen et al. (2013) showed

how this technique is particularly interesting and particularly

promising for studies of the mesosphere.

The Heating facility remained essentially unchanged

through the 1990s. An operating licence was obtained to

allow frequency-stepping experiments around harmonics of

the gyro-frequency. There was an upgrade of the computer

from the original Commodore PET to a Microsoft Windowsbased personal computer system in 1999, when the original

BASIC control program was converted to Hewlett Packard

BASIC, and the more modern computer allowed RF synthesizer and transmitted HF parameters to be stored in a

digital log. Previously, the transmitter settings had been

recorded largely in a hand-written log book. There were minor changes made to some of the control system, such as a

programmable step change in the control grid bias voltage

during long (> ca.1 s) “RF off” intervals such that the quiescent current in the transmitter tubes dropped from about 6

to 1 A (at 10 kV in each of 12 transmitters!) to save on electricity power consumption. One saves most on power consumption when the high voltage is switched off so that no

quiescent current flows through the tube, but this had to be

done manually by pushing 12 buttons that actuated 12 large

relays, something that is undesirable for non-transmitting intervals of a few seconds, tens of seconds, or a few minutes,

which are rather commonly used modulation periods. The

cost of electric power for Heating operation, especially when

experiments required Heating and the VHF and UHF radars,

was a major economic concern in the 1990s at a time when

there were some EISCAT associates who were advocating

for the closure of the Heating facility to save money.

Around 2005, plans were made to upgrade the synthesizers

to direct digital synthesis (DDS) and the associated computer

control to a unix-based system. Apart from replacing ageing hardware, a major motivation was to allow fast frequency

changes of the HF pump wave which were increasingly requested in order to examine the ionospheric response to HF

pumping at and near harmonics of the ionospheric gyrofrequency. Previously, frequency changes required a severalminute-long tuning and phasing procedure under computer

control, as the HP synthesizers started with a random phase

value for any frequency change. The digital system would

allow setting of phases to any desired values practically inFigure 6. The Heating facility console in the control room as it was

in 2007, with the first author at the controls. Six columns of meters,

lights, and push buttons on each side show the status and are used

to control each of the 12 transmitters. The 12 commercial RF synthesizers in the middle of the console have been replaced by digital

synthesizers in the transmitter hall, and the space is now filled with

large computer screens. (Photo credit: Michael T. Rietveld)

stantaneously. The final system, which was taken into regular

use in 2009, used some hardware and much software that the

EISCAT IS radars had implemented in the mid-1990s when

the ESR was built. This upgrade was a major effort involving the expertise of EISCAT staff from Tromsø as well as

the other two mainland sites, the EISCAT headquarters in

Kiruna, Sweden, and Sodankylä in Finland. This upgrade and

further improvements to the Heating system are described in

Rietveld et al. (2016). From 2012, even more functionality

has been developed such that the status of many transmitter

and array parameters that were only indicated by lights or

controllable by buttons are now monitored and set by computer. Figure 6 shows the console in the control room before

the upgrade. The main difference after the upgrade is the replacement of the 12 original synthesizers in the central part

with large computer screens that are now used to control and

monitor the facility’s operation and observe some scientific

results in real time.

In 2013, a modification was made to the coaxial switches

that fed Array 3 to allow receivers to be connected to that

array. The motivation for this was to try and receive magnetospheric echoes, for example, from ion acoustic turbulence

excited by auroral processes such as has been observed by

the VHF and UHF IS radars (Rietveld et al., 1996a). Previously, related experiments had been tried using Heating

as a transmitter and the large HF radio telescope, UTR2, in

Ukraine as a receiver, although without results. As the modified Array 1 and Array 3 cover the same frequency range, one

could transmit on Array 1 and receive on Array 3, albeit with

different antenna gains and, hence, beam widths. The first

Hist. Geo Space Sci., 13, 71–82, 2022 https://doi.org/10.5194/hgss-13-71-2022

M. T. Rietveld and P. Stubbe: History of the Tromsø ionosphere heating facility 79

version of a receiver connected to Array 3 for radar work

is described in Rietveld et al. (2016), where fixed-length

phasing cables were used to combine the signals from the

six rows of orthogonal antennas into two receiver channels.

Since 2017, each individual row of antennas is connected to

a digital receiver allowing beam forming of the received signal in the north–south plane. This receiving system seems to

work well for mesospheric echoes, but echoes from the magnetosphere have not been detected to date. Using Array 3 as

a receiving antenna has some weaknesses, such as the aluminium connectors in the feeder lines where an oxide layer

may adversely affect weak radio signals, although this layer

is burnt through by the powerful radio wave on transmission

for which it was designed.

The Heating facility was only intended to operate for a

limited time of about 10 years; thus, 40 years after construction, it was inevitable that some parts of the system had aged

to a critical point or that spare parts had become unobtainable. One key component is the transmitting tube in each

of the 12 power amplifiers. The original tube was no longer

produced after 1980, but a good number of spares allowed

operation at near-full-power level until recently. Very few

tubes failed completely, but after about 12000 h of filamenton time over the lifetime of Heating, several were slowly delivering less power. A few tubes were sent to firms in the

USA to be rebuilt, but the success rate was poor. In searching for an alternative tube that required minimal modification

to the transmitters, it was found that the RS2054SK tetrode

was almost compatible with the existing transmitter, and this

tube type was still manufactured in Europe and in China. Although it was a drop-in replacement in the tube socket, the

new tube required a different filament voltage and a slow

ramping up and down of the voltage so that several modifications to the transmitter had to be made. In 2018, the

first of the new tubes entered operation, and two transmitters

presently use the new tubes with a third ready to be similarly

modified.

Another ageing problem that first appeared around 2008

was in the modified Array 1. The feed cables to the antennas

in this array were different from the original design in that,

instead of towers made of aluminium coaxial cable feeding

each antenna, commercial twin-wire flexible cable was used.

Starting in 2008, an increasing number of the 288 feed points

at the antenna failed during transmission through burning insulation and fire, often resulting in the collapse of the whole

feed point and antenna to the ground and sometimes resulting in a dramatic grass fire. The cause of this failure was a

mystery for a long time, and a total of 17 feed cables and the

centre parts of the antennas had required laborious repairs

by 2017. In 2015, the cause of this failure was found to be

metal fatigue in the flexible twin-wire braided-copper cable

where it was anchored to the fixed centre of the antenna, with

the rest of the feed cable from near the ground having been

free to move slightly in the wind for about 20 years. Many

of the anchoring guy ropes which should have minimized

movement of the cable in the wind had broken and were not

repaired. The wind-induced movement of the cable caused

many of the braids to break such that the cross-sectional area

of the cable was reduced to the point that the high-power RF

caused overheating or arcing across the final break, resulting in burning of the insulation. The solution was to bypass

the anchor point with a short piece of wire crimped to the

feed wires on each of the 144 antenna centres on the 12 m

tall masts, a job which took several summer seasons and required EISCAT to buy a lift to safely implement the repairs.

It is hoped that this solution is robust enough for the remaining lifetime of the Heating facility. Figure 7 shows the repair

work in Array 1, where the different feed cables (compared

with those in Fig. 3) are clearly visible.

7 Present status and future

The main hardware of Heating, the transmitters, feed lines,

and antennas, have remained essentially unchanged since

1990, apart from the computer control and RF synthesizer

upgrades described above. The user community has changed

with time, with some users and groups changing field, but

there are also new users entering the field. With the closure of other facilities like the HIPAS (HIgh Power Auroral Stimulation) Observatory in Alaska (Wong et al., 1990)

and SPEAR (Space Plasma Exploration by Active Radar)

on Svalbard (Robinson et al., 2006) as well as the hopefully temporary closure of the Arecibo heating facility, the

only sites with working HF ionospheric heating facilities are

HAARP (High-frequency Active Auroral Research Program)

in Alaska (Pedersen and Carlson, 2001) and Sura in Russia (Belikovich et al., 2007). On 1 December 2020, after

57 years of usage, Arecibo Observatory’s 900 t platform containing transmit–receive feeds fell ∼ 150 m and crashed into

the 305 m diameter reflector dish. This halted IS radar, HF

heating, planetary radar, and radio astronomy observations

at the observatory. Full or partial recovery plans are currently

under consideration by the US National Science Foundation.

Complete decommissioning appears unlikely, and a modest

HF facility is currently being constructed at Arecibo to keep

HF heating research moving forward. However, none of these

other installations will have an IS radar as a diagnostic instrument in the foreseeable future, which makes the Tromsø HF

heater a unique and valuable facility for the world.

Groups from all the EISCAT Associates have been regular users of the Heating facility. In recent years, researchers

from China – the China Research Institute of Radio Wave

Propagation (CRIRP) became an EISCAT Associate in 2007

– have become important regular users. A large international community of scientists have been able to use the

Tromsø HF facility, especially in the last decade, as nonEISCAT Associates could either buy time or apply for a

limited number of free hours on either the IS radar, heater,

or both via a peer-review programme. An excellent examhttps://doi.org/10.5194/hgss-13-71-2022 Hist. Geo Space Sci., 13, 71–82, 2022

80 M. T. Rietveld and P. Stubbe: History of the Tromsø ionosphere heating facility

Figure 7. Repair work to one of the 12 m high antennas out of

144 such antennas in Array 1 to bypass existing and potential weak

points in the twin-feed cable connection to the antenna centre. The

original 23 m wooden masts are visible in the background. Note the

different support mast and the different feed lines compared with

the original design as used in Array 2 and Array 3, shown in Fig. 3.

(Photo credit: Michael T. Rietveld)

ple of fruitful scientific results from heating experiments by

a non-EISCAT Associate is a 25-year collaboration with a

group from the Russian Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute (Blagoveshchenskaya et al., 2020). Other long-term

users were researchers from the Polar Geophysical Institute, in Murmansk, Russia, and from the Institute of Radio Astronomy in Ukraine. A description of the various

scientific results that have been obtained from the Heating facility is beyond the scope of this paper. The number of accumulated publications from the Tromsø heating

facility amounts to more than 490, and these papers are

listed on the EISCAT publications web page (https://eiscat.

se/scientist/publications/heating-publications/, last access: 3

March 2022). Streltsov et al. (2018) discuss many of the

physical problems that are topics of present and future research in the field of active experiments using high-power

radio waves. Some of the interesting phenomena to explore

are narrowband SEE (stimulated Brillouin scatter), artificial

ionization, unexplained X-mode effects, and the irregularities postulated to explain wide-altitude ion line enhancements sometimes known by the acronym WAILES (Rietveld

and Senior, 2020).

The Tromsø heating facility has not been overly troubled

by adverse publicity or conspiracy theories. The experiments

conducted at the Tromsø facility were always open, and all

publications resulting from it appear in the open literature;

we believe this is true for nearly all of the experiments performed at the other facilities as well. Nevertheless, over the

years, there have been exaggerated and false claims and conspiracy theories made about some of the experiments that are

possible with heating facilities like HAARP in Alaska and

Heating in Tromsø.

The site in Ramfjordmoen is about to undergo a major

change when the EISCAT UHF and VHF radars are decommissioned and EISCAT_3D, the next-generation IS radar

(McCrea et al., 2015), starts operation, with the core site in

nearby Skibotn. Since the retirement of the first author, the

Heating facility has been led and run by Erik Varberg. The

Heating facility is planned to remain in operation for experiments with the new radar which will offer unprecedented

insights into HF-induced phenomena. The improved spatial

resolution and the ability to quickly steer the beam of the new

radar electronically or to have multiple beams should help

probe the horizontal spatial properties of HF-induced irregularities. There is one disadvantage to not having the HF facility and the radar co-located, namely the radar cannot probe

in the field-aligned direction along the heater beam in the F

region. This problem may be overcome by resurrecting, in a

slightly modified form, the east–west tilting hardware built

for the HERO rocket campaign in the 1980s mentioned earlier. Most of the switching hardware still exists, but new aluminium coaxial phasing cables would need to be made and

installed. The possibility of building a new heater nearer Skibotn is also being investigated.

Data availability. No data sets were used in this paper. All citations appear in the reference list.

Author contributions. MTR wrote most of the paper, and PS provided additions and corrections.

Hist. Geo Space Sci., 13, 71–82, 2022 https://doi.org/10.5194/hgss-13-71-2022

M. T. Rietveld and P. Stubbe: History of the Tromsø ionosphere heating facility 81

Competing interests. The contact author has declared that neither they nor their co-authors have any competing interests.

Disclaimer. Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains

neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and

institutional affiliations.

Acknowledgements. In addition to the people mentioned in this

paper, we thank the large number of unnamed staff from MPAe and

EISCAT as well as other collaborators, who helped build, operate,

and maintain this remarkable scientific facility. EISCAT is an international scientific association presently supported by research organizations in China (CRIRP), Finland (SA), Japan (NIPR and STEL),

Norway (NFR), Sweden (VR), and the United Kingdom (NERC).

Review statement. This paper was edited by Kristian Schlegel

and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

References

Belikovich, V., Benediktov, E. A., Tolmacheva, A. V., and

Bakhmet’eva, N. V.: Ionospheric research by means of artificial

periodic irregularities, ISBN 3-936586-03-9, Göttingen, Copernicus GmbH, 2002.

Belikovich, V. V., Grach, S. M., Karashtin, A. N., Kotik, D. S., and

Tokarev, Yu. V.: The SURA facility: study of the atmosphere and

space, Radiophys. Quantum El., 50, 7, 497–526, 2007.

Blagoveshchenskaya, N. F.: Perturbing the High-Latitude Upper

Ionosphere (F Region) with Powerful HF Radio Waves: A 25-

Year Collaboration with EISCAT, Radio Science Bulletin, 373,

40–55, 2020.

Brändström, B. U. E., Leyser, T. B., Steen, Å., Rietveld, M. T., Gustavsson, B., Aso, T., and Ejiri, M.: Unambiguous evidence of HF

pump-enhanced airglow at auroral latitudes, Geophys. Res. Lett.,

26, 3561–3564, 1999.

Chilson, P. B., Belova, E., Rietveld, M. T., Kirkwood, S., and

Hoppe, U.-P.: First artificially induced modulation of PMSE using the EISCAT heating facility, Geophys. Res. Lett., 27, 3801-

3804, 2000.

Czechowsky and Rüster: 60 Jahre Forschung in Lindau (in German), Copernicus Publications, Göttingen, ISBN 979-3-936586-

65-7, 2007.

Fejer, J. A. and Kopka, H.: The effect of Plasma instabilities on the

ionospherically reflected wave from a high power transmitter, J.

Geophys. Res., 86, 5746–5750, 1981.

Haerendel, G.: History of EISCAT – Part 4: On the German contribution to the early years of EISCAT, Hist. Geo Space. Sci., 7,

67–72, https://doi.org/10.5194/hgss-7-67-2016, 2016.

Holt, O.: History of EISCAT – Part 3: The early history

of EISCAT in Norway, Hist. Geo Space. Sci., 3, 47–52,

https://doi.org/10.5194/hgss-3-47-2012, 2012.

Kopka, H., Stubbe, P., and Zwick, R.: On the ionospheric modification experiment projected at MPI Lindau: Practical realization,

AGARD Conference Proceedings, 192, 10.1–10.7, 1976.

Leyser, T. B.: Stimulated electromagnetic emissions by highfrequency electromagnetic pumping of the ionospheric plasma,

Space Sci. Rev., 98, 223–328, 2001.

McCrea, I., Aikio, A., Alfonsi, L., Belova, E., Buchert, S.,

Clilverd, M., Engler, N., Gustavsson, B., Heinselman, C.,

Kero, J., Kosch, M., Lamy, H., Leyser, T., Ogawa, Y., Oksavik, K., Pellinen-Wannberg, A., Pitout, F., Rapp, M., Stanislawska, I., and Vierinen, J.: The science case for the EISCAT_3D radar, Progress in Earth and Planetary Science, 2, 21,

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-015-0051-8, 2015.

Pedersen, T. T. and Carlson, H. C.: First observations of

HF heater produced airglow at the High Frequency Active Auroral Research Program facility: thermal excitation and spatial structuring, Radio Sci., 36, 1013–1026,

https://doi.org/10.1029/2000RS002399, 2001.

Rietveld, M. T. and Senior, A.: Ducting of incoherent scatter radar

waves by field-aligned irregularities, Ann. Geophys., 38, 1101–

1113, https://doi.org/10.5194/angeo-38-1101-2020, 2020.

Rietveld, M. T., Kohl, H., Kopka, H., and Stubbe, P.: Introduction

to ionospheric heating at Tromsø-I. Experimental overview, J.

Atmos. Terr. Phys., 55, 577–599, 1993.

Rietveld, M. T., Collis, P. N., van Eyken, A. P., and Løvhaug, U. P.:

Coherent echoes during EISCAT UHF Common Programmes, J.

Atmos. Terr. Phys., 58, 161–174, 1996a.

Rietveld, M. T., Turunen, E., Matveinen, H., Goncharov, N. P., and

Pollari, P.: Artificial Periodic Irregularities in the Auroral Ionosphere, Ann. Geophys., 14, 1437–1453, 1996b.

Rietveld, M. T., Wright, J. W., Zabotin, N., and Pitteway,

M. L. V.: The Tromsø Dynasonde, Polar Sci., 2, 55–71,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2008.02.001 2008.

Rietveld, M. T., Senior, A., Markkanen, J., and Westman, A.: New

capabilities of the upgraded EISCAT high-power HF facility, Radio Sci., 51, 1533–1546, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016RS006093,

2016.

Robinson, T. R., Stubbe, P., Thidé, B., Rietveld, M., and Mjølhus, E.: A New Heating Facility for EISCAT: Scientific Case,

EISCAT Technical Report, https://eiscat.se/wp-content/uploads/

2021/05/Robinson_report_1989.pdf (last access: 3 March 2022),

1989.

Robinson, T. R., Yeoman, T. K., Dhillon, R. S., Lester, M., Thomas,

E. C., Thornhill, J. D., Wright, D. M., van Eyken, A. P., and McCrea, I.: First observations of SPEAR induced artificial backscatter from CUTLASS and the EISCAT Svalbard radar, Ann. Geophys., 24, 291–309, 2006.

Rose, G., Grandal, B., Neske, E., Ott, W., Spenner, K., Holtet,

J., Måseide, K., and Trøim, J.: Experimental Results From the

HERO Project: In Situ Measurements of Ionospheric Modifications Using Sounding Rockets, J. Geophys. Res., 90, 2851–2860,

1985.

Senior, A., Rietveld, M. T., Honary, F., Singer, W., and

Kosch, M. J.: Measurements and modelling of cosmic

noise absorption changes due to radio heating of the

D-region ionosphere, J. Geophys. Res., 116, A04310,

https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JA016189, 2011.

Streltsov, A. V., Berthelier, J.-J., Chernyshov, A. A., Frolov, V.

L., Honary, F., Kosch, M. J., McCoy, R. P., Mishin, E. V.,

and Rietveld, M. T.: Past, Present and Future of Active Radio

Frequency Experiments in Space, Space Sci. Rev., 214, 118,

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-018-0549-7 2018.

https://doi.org/10.5194/hgss-13-71-2022 Hist. Geo Space Sci., 13, 71–82, 2022

82 M. T. Rietveld and P. Stubbe: History of the Tromsø ionosphere heating facility

Stubbe, P.: Review of ionospheric modification experiments at

Tromsø, J. Atmos. Terr. Phys., 58, 349–368, 1996.

Stubbe, P., Kopka, H., and Rose, G.: Rocket experiments in conjunction with the ionospheric modification experiment in northern Norway, edited by: Halvorsen, T. and Battrich, B., Proceedings of Esrange Symposium, Ajaccio, 24–29 April, ESA SP-135,

107–111, 1978.

Stubbe, P., Kopka, H., Brekke, A., Hansen, T., Holt, O., Dowden, R.

L., Jones, T. B., Robinson, T. R., Lotz, H.-J., and Watermann, J.:

First results from the Tromsø ionospheric modification facility,

AGARD Conference Proceedings, 295, 16.1–16.9, 1980.

Stubbe, P., Kopka, H., Lauche, H., Rietveld, M. T., Brekke, A.,

Holt, O., Jones, T. B., Robinson, T., Hedberg, Å., Thidé, B., Crochet, B., and Lotz, H.-J.: Ionospheric modification experiments

in northern Scandinavia, J. Atmos. Terr. Phys., 44, 1025–1041,

1982.

Stubbe, P., Kopka, H., Thidé, B., and Derblom, H.: Stimulated electromagnetic emission: A new technique to study the parametric

decay instability in the ionosphere, J. Geophys. Res., 89, 7523–

7536, 1984.

Stubbe, P., Kopka, H., Rietveld, M. T., Frey, A., Høeg, P., Kohl,

H., Nielsen, E., Rose, G., LaHoz, C., Barr, R., Derblom, H.,

Hedberg, Å., Thidé, B., Jones, T. B., Robinson, T., Brekke, A.,

Hansen, T., and Holt, O.: Ionospheric modification experiments

with the Tromsø heating facility, J. Atmos. Terr. Phys., 47, 1151–

1163, 1985.

Tellegen, B. D. H.: Interaction between radio waves, Nature, 131,

840, https://doi.org/10.1038/131840a0, 1933.

Thidé, B., Kopka, H., and Stubbe, P.: Observations of stimulated

scattering of a strong high-frequency wave in the ionosphere,

Phys. Rev., Lett., 49, 1561–1564, 1982.

Utlaut, W. F.: Foreword to special issue on ionospheric modification, Radio Science, special issue, 9, 881–1090, 1974.

Vierinen, J., Kero, A., and Rietveld, M. T.: High latitude artificial periodic irregularity observations with the upgraded EISCAT heating facility, J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phy., 105–106, 253–

261, 2013.

Wannberg, G.: History of EISCAT – Part 5: Operation and development of the system during the first 2 decades, Hist. Geo Space.

Sci., 13, 1–21, https://doi.org/10.5194/hgss-13-1-2022, 2022.

Wong, A. Y., Carroll, J., Dickman, R., Harrison, W., Huhn, W.,

Lure, B., McCarrick, M., Santoru, J., Schock, C., Wong, G., and

Wuerker, R. F.: High-power radiating facility at the HIPAS Observatory, Radio Sci., 25, 1269–1282, 1990.

+ There are no comments

Add yours